Our CEO, Tom Chance, writes about our hopes for a reformed Community Right to Buy, and for a wider government strategy to use community ownership to promote sustainable development.

We’re very excited that the Devolution Bill, trailed in the King’s Speech, is slated to include a Community Right to Buy. We’ve been calling for this for many years.

But there is a risk that it simply extends the Localism Act’s Community Right to Bid, warts and all.

That right has been positive, but suffers from at least three major flaws:

- The six month window for bids, and the lack of a first right of refusal, make it toothless and hard for most communities to use.

- It can only be used to buy Assets of Community Value, defined as assets currently or recently used for social benefit.

- The right to bid excludes buying housing or developing housing, which often forms a key part of the business plan for mixed-use schemes – think community space in the ground floor, flats above.

These flaws were replicated in the criteria for the Community Ownership Fund.

For many of our members, especially in the most deprived communities, the issue is that they lack important assets. There are none to save! Often, land and buildings in key locations are lying empty, derelict, or underused, in an area with pressing social, economic or environmental needs. They want to buy land and buildings to develop or convert them into new uses that will sustain their community life.

Their needs may be broader than the ‘social benefits’ described as social wellbeing and cultural, recreational and sporting ‘social interests’. Like workspace for small businesses. Or affordable homes.

Here are some fantastic CLT projects that fall outside the scope of these community rights and funds.

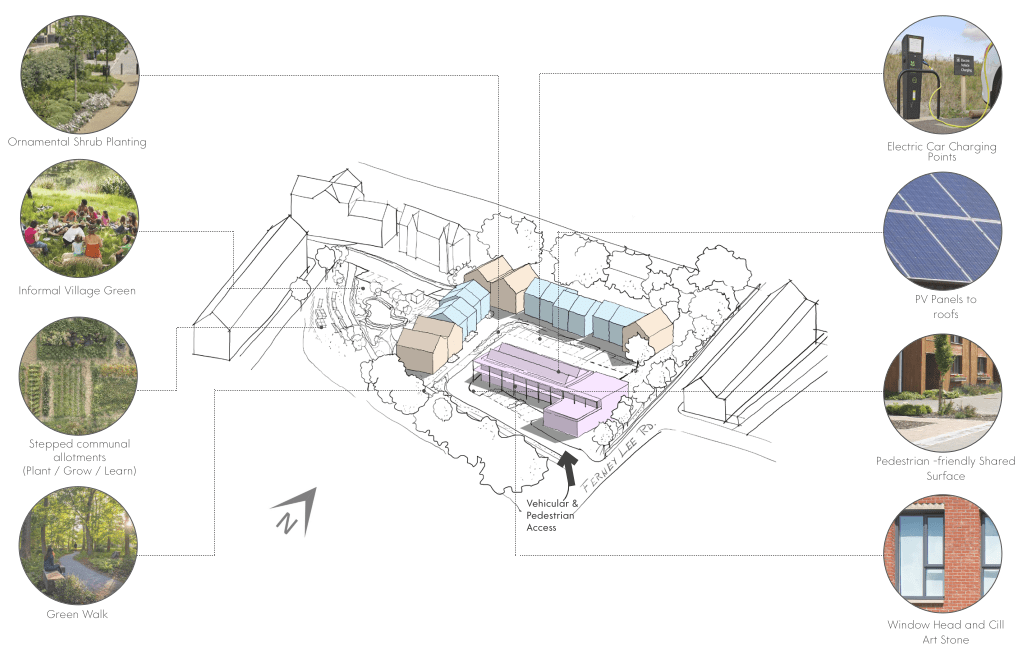

Calder Valley CLT’s plans to develop a new enterprise centre with affordable rented homes and offices on the site of the former Ferney Lee Home for Older People.

Hastings Commons’ acquisition of a derelict office block which it turned into 6 living rent flats, 20 commercial units, and dedicated desks for start-ups, small business and local entrepreneurs.

Nudge Community Builders’ acquisition of 4000sqm of empty buildings in Plymouth creating space for 25 small businesses and a wealth of community activity.

Mayday Saxonvale and Frome Area CLT’s joint plans to redevelop a large ex-industrial site in Frome into homes, workspace and community facilities, in the teeth of a detrimental competing bidder

The Hastings case illustrates how useless these community rights have been. Hastings Commons tried to get another building, the Observer Building, listed as an Asset of Community Value. But it was refused for technical reasons that you can find on the council’s website. The same page lists other unsuccessful applications, all killed off because of the narrowly framed definition of Asset of Community Value. Of course Hastings Commons managed to buy the Observer Building anyway, along with eight other buildings with more in their sights.

Indeed, of the more than 100 completed CLT projects across England, only one has used any of the 2011 Localism Act community rights!

In Scotland, the Community Right to Buy is much better.

It enables communities to buy any land, with any existing use, so that it can then be used (in any way) to further the sustainable development of the community. There are a few minor exceptions to do with government land, oil fields and the like.

The concept of sustainable development is defined really broadly to encompass all manner of services, infrastructure, the reduction of social disadvantage, enhanced local environment, job creation, etc. The criteria align with wider public duties, and approaches to spatial planning and economic development. The Scottish Community Right to Buy invites communities to bid on the basis of a proposal for better use, not its existing use.

The Scottish land fund then aids the acquisition with a similarly broad set of criteria.

I’ve spoken with my counterparts in Community Land Scotland over the years, who see the framework there as hugely important. Partly in providing a back-pocket threat to aid negotiated purchases (which most buyouts have been). But also in framing and legitimising community ownership in the broadest sense as part of a national strategy for sustainable development.

In England, the era of the Localism Act has seen community ownership more narrowly framing as saving pubs and bailing out austerity-struck councils.

Going by what Labour has said elsewhere, ministers are minded to fix the first flaw — something like giving communities a presumptive right to buy assets of community value with a 12 month window. But we have heard little of these other issues. The briefing for the King’s Speech frames the reform very much in terms of buying assets of community value like shops, pubs and community spaces.

As we set out in our manifesto, if the government is serious about empowering communities to play their part in national renewal, it needs to do better, to think bigger.

A truly powerful Community Right to Buy and Community Ownership Fund also need to be joined up with other tools, such as a Community Wealth Fund to build capacity in deprived communities; a strategy to develop enabling intermediaries able to buy and develop assets with communities, rather than leaving communities to do all the heavy lifting; modernising the rules for best consideration so public assets are sold at a value that makes it viable to deliver on policy objectives set out in the Local Plan, including affordable housing; a review of how these tools connect with funds like the UK Shared Prosperity Fund and the Affordable Homes Programme; and, as the Co-op Party’s Community Ownership Commission proposed, giving a stronger role to local authorities to co-develop local growth plans with local communities and support community ownership where it furthers those plans.

As the Welsh government review their own community rights framework, we will be pushing for a similarly broad approach. In recent years we’ve urged that they follow the Scots, not the English, in creating frameworks for community rights.

These and many other ideas are on our agenda over the coming years. A good start would be to redraw the Community Right to Buy – away from its Big Society roots and into a genuinely powerful tool for every community to lead the national renewal, rooted in their local area.