Our CEO, Tom Chance, writes on the potential of Community Land Trusts to help build much more social housing in England, and argues that the next government will be more able to meet its housing targets with a more diverse housebuilding market.

Lots of think tanks and political advisers are currently trying to answer the question: how could the next government build much more social housing?

We’ve not built it in large numbers since the 1970s, and thanks to Right to Buy, disposals and demolitions we have a lot less of it now than we did then, even as the population and need has grown.

Could Community Land Trusts (CLTs) contribute to turning this around?

You may not be aware that three quarters of CLT homes are for social rent and affordable rent. Here’s how the current stock breaks down by three main tenure groups:

social rent

affordable rent

affordable ownership

CLTs would probably have provided most of the 750 affordable rent homes at social rent levels if only grants policy allowed it.

The story is similar with the pipeline of homes CLTs hope to build, with social and affordable rent making up 75% of the 7,000 or so homes currently recorded in our database. The same percentage of 11,818 homes in the wider community led sector’s pipeline in a 2021 study we commissioned were for social and affordable rent.

But the questions I want to try to answer are: how many could CLTs provide in the next five years, and how many might they be providing annually by the end of the next Parliament?

The very conservative answer

Most CLTs successfully completing low rent housing are choosing to partner with housing associations, and most of those are being supported by proficient regional enablers.

One of those enablers, Middlemarch CLH, recently completed some research as part of our pilot CLH Growth Lab looking at how its model could be scaled up across the country. Alongside that, we did some modelling with Middlemarch and five other regional enablers, examining the pipeline of projects they are supporting.

To complete most of these projects in the coming years requires two conditions:

- Capital grant levels sufficient to make social rent viable, including in rural areas and urban brownfield that might have higher ‘abnormal’ costs.

- Bringing forward some of that grant in the form of pre-development funding for the regional enablers, which is then mostly knocked off the capital grant requirement later on (so is close to fiscally neutral).

If these could be achieved, then I’d be confident in saying that CLTs could start on site at least an additional 1,800 social rent homes in 120 schemes in the course of the next parliament, or 360 per year on average.

The slightly less conservative answer

Beyond those projects, there are many more that currently lack a proficient enabler. This means that some are less likely to make progress, more likely to make mistakes, and may find it harder to attract a partner housing association or developer.

To complete these, we require the same two conditions as above plus one or two more:

- Investment in developing more regional enablers, such as through the CLH Growth Lab and Growth Fund we have proposed with UKCN and CCH.

- Optionally a revenue grant scheme that groups can access on a project-by-project basis; like the fund for enablers a lot of this would be fiscally neutral, but would most likely see a higher ‘sunk cost’ in failed projects.

With those conditions in place, on the basis of projects currently in the pipeline I would estimate that CLTs could start on site an additional 4,300 social rent homes, or 860 per year on average over the Parliament. This would look more like a ramp, with little delivery initially but many more starts towards the end.

The ambitious answer

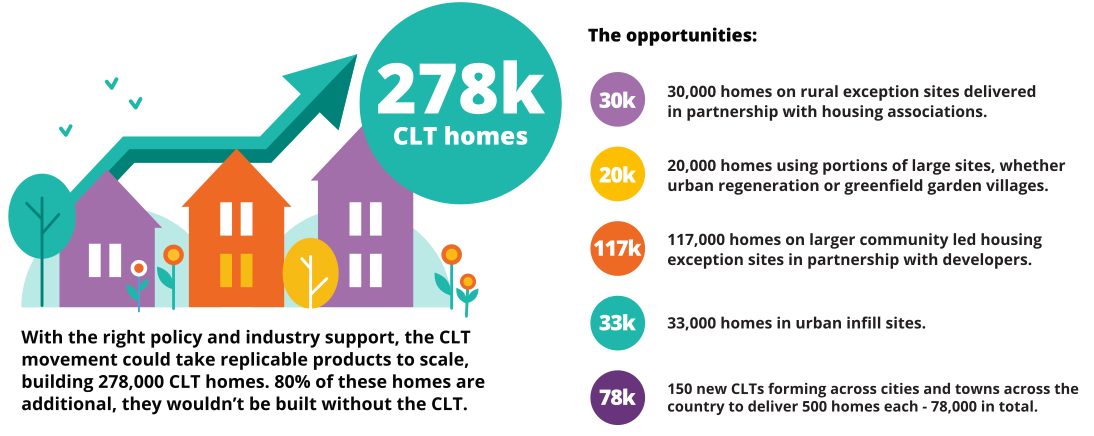

In our State of the Sector report, published in March 2023, we put some numbers on the potential of scalable models for CLT housing projects.

Achieving that scale of provision would require the full implementation of our 2024 manifesto, encompassing the financing and enabling policies mentioned above, plus:

- Planning reforms including turbocharging community led exception sites, allocations of sites for community led development, and injecting community stewardship into large sites, along with reforms to tackle ‘hope value’ in allocated sites.

- Enabling tenants and communities to take control of all or part of urban regeneration projects, including estate regeneration, through a ballot.

- Leasehold reforms to protect the ability of CLTs to own the freehold of social rent homes and lease them to other providers, protecting them from the right to buy etc.

- In some cases, a Community Right to Buy to bring more dilapidated and underused assets into community hands.

The point behind some of those is that CLTs have been shown by recent academic research to be more likely to achieve genuine affordability, measured in terms of what residents actually earn and are able to pay in rent. So by increasing the proportion of the housebuilding market that CLTs play a role in, you are likely to increase the provision of social housing – if grant levels etc enabled this.

These 278,000 homes broaden out to a much wider variety of tenures. Moreover, not all of the homes would be ‘additional’ – many would simply see planned homes coming into the ownership and stewardship of CLTs. They were also across the UK, but the next housing minister will only have responsibility for England. So here are my estimates for each, in England, using ONS data on settlement numbers:

- CLTs and housing associations in villages – 15 homes every ten years in one quarter of the 10,000 parish and town council areas, of which 80% would be social rent and all additional = 3,000 per year.

- CLTs and developers on community-led exception sites – 75 homes every ten years adjacent to 993 small and large towns and the same in 5% of villages, of which 25% would be social rent and 80% additional = 2,240 per year.

- CLTs in large sites – hard to pin down over the next five years given long timescales, and arguably few would be additional social rent, so assume zero.

- CLT-led suburban infill – 33,000 homes over 15 year cycles, of which 50% are social rent and all additional = 1,100 per year.

- CLTs as developers – 500 homes every 20 years in the 108 large towns and cities, of which 60% are social rent and 80% additional = 1,296 per year.

- TOTAL: 7,636 per year

Given the variety of sources, it’s very hard to estimate how many would be funded through s106 deals (or the Infrastructure Levy, or whatever replacement comes in) and how many would need capital grant; and of those, how much.

It would also take at least five years to ramp up to that annual figure, given all the reforms and capacity building required.

So what?

Using the above calculations, we arrive at three scenarios for annual social housing supply from CLTs, expressed in terms of numbers of homes per year and then that as a percentage of the 90,000 annual target:

very conservative

%

conservative

%

ambitious

%

It’s not obvious how we provide 90,000 new social rent homes each year, even if HM Treasury can be persuaded to invest the money. Councils and housing associations will take time to gear up.

They have also historically neglected smaller and rural communities, and after years of mergers and consolidation few housing associations are interested in the work and risk in developing smaller sites and taking smaller s106 contributions. But many have been willing to partner with CLTs, if communities – with enablers – can bring forward projects with an option on the land and a planning consent.

The lack of diversity in the housebuilding industry has also long been understood as a constraint on the total number of homes being built (or brought back into use).

So even a 1% modest contribution should be looked at seriously, and getting up to 8.5% makes this a significant part of the solution. If you add in further opportunities for housing co-operatives, mixed tenure cohousing communities and other community models, it looks all the more compelling.

While I’d hope it is nearer the upper end of that range, there are particular reasons for valuing the CLT contribution:

- They are overwhelmingly in places others find hard to develop – rural areas, suburban and urban infill, on the edges of small towns, deprived coastal towns, and repurposing empty properties – making valuable contributions in communities that are likely to be overlooked otherwise.

- The homes will stay as social rent – they are all protected from the voluntary and statutory Rights to Buy, the Right to Shared Ownership, and routes to leasehold enfranchisement.

- Most CLTs don’t stop at housing (and some don’t start there). So this programme would leave a legacy of hundreds of revenue-generating community organisations across the country, able to develop more housing and branch out into protecting and providing other important assets – green space, community centres, workspace, pubs, shops, etc.

- Research shows that by giving communities agency through CLTs, you can also help to build pride in place, improve social cohesion, and reduce loneliness.

Politicians and advisers looking for a way to achieve all of this need look no further than our manifesto, and then come to our summer conference on the 21st June where we will be talking about this in the context of rural partnerships, large-scale housebuilding and urban renewal.