Our chief executive, Tom, reflects in this essay on why we should rethink the role of the Community Land Trust in land, development and housing – to move to a modular and layered understanding of places and the partnerships that enable sustainable communities. An earlier and shorter version of this essay was published by The Developer magazine.

As a geeky teenager, and long before I got interested in housing and Community Land Trusts, I was involved with the digital commons. I volunteered with free software projects, worked on a prototype of Wikipedia and then got involved in the early days of Creative Commons.

Websites like Wikipedia, and indeed most of the software that runs the internet, were built on three principles. In this essay I want to apply them to housing and places in order to persuade you to reimagine the role of Community Land Trusts.

The three principles

Doug McIlroy, Boston, Massachusetts, 2015

The first principle was the commons, and the subversion of copyright through ‘copyleft’ licenses:

share intellectual property and let others use, copy and adapt it, so long as they feed those adaptations back into the commons

The second was the open source method:

collaborate openly because given enough eyes, all problems are shallow; treat your users as co-developers; release early, release often; and so on.

The third principle, that shaped both the digital commons and open source was coined by Doug McIlroy in 1978, and is known as the Unix philosophy:

each tool should do one thing, do it well, and work together with other tools.

So you should design for simplicity by looking for ways to break up complex systems into small, straightforward cooperating pieces. The ability to connect many small tools that do their jobs really well is better than having a single tool that does everything poorly. It’s much easier to fix and improve each tool in isolation than it is trying to find the problem with a huge, sprawling multitool. All of this works especially well when many people, many organisations, collaborate on a shared pool of intellectual property.

For example, there is a tool to read the contents of a file, which sends its output to a second tool which can search the text, which sends the search results to a third tool which sorts them alphabetically, and a fourth which saves them into a new file.

Forty years ago you’d be typing all of this into a black and white command line.

Nowadays it all happens seamlessly behind the scenes, including right now as you read this blog on your web browser – hundreds of tools are combining to show you what I’ve written. Tools that are built collaboratively by thousands of people, shared in a commons using copyleft licenses.

Software built on these principles runs most of the internet. It’s the backbone of Apple’s operating system and Android phones.

Applying this to housing

But in the world of affordable housing we’re stuck in a monolithic mindset.

Kwajo Tweneboa, housing activist

Think about a large housing association as a complex multitool. It maintains homes, manages tenants and leaseholders, buys land, creates masterplans for regeneration and new development, consults with the wider local community, supports residents with welfare and employment, provides small grants to community groups and often more besides.

Generally speaking, housing associations do a good job. But there are also many examples where they’re not doing all of these jobs well. Like the housing associations lobbying to curb the ability of tenants to make disrepair claims in courts, because it was affecting their financial performance. Or the appalling stories of disrepair exposed by journalists at ITV and activists like Kwajo Tweneboa, often where the landlords have taken their eye off maintaining the homes because they are so focused on major regeneration and development programmes.

Their standard practice is also not collaborative. They don’t co-design and co-produce their new developments, their management services, with tenants and residents, and with the local communities they operate in. There are pockets of innovation but they’re exceptions to the rule. Their assets – the land, buildings, people – are what techies would call a ‘walled garden’ they control and tend, rather than a commons in which they are a lead gardener.

What if we could split out all the different jobs the housing association does into different tools, put them into a commons, and make the different tools work well together?

What if affordable housing was like Unix?

A very common model of partnership between CLTs and housing associations takes a first step towards this, splitting out those roles into two parties:

- CLT – own the land, steward the wider community’s interest, engage with and give voice to the community

- Housing association – finance, build and maintain the homes, manage the tenants, provide welfare services, etc.

Making the partnership work is no easy task, but the results are often award-winning. This model puts the land and buildings into a collaborative commons in which the wider community (frequently but not always including prospective tenants) co-design and co-produce the housing. As a rule, it doesn’t tend to involve further collaboration on the housing management and maintenance – the CLT leaves the housing association to do this in their normal way.

We could take it further, breaking it up into smaller cooperating pieces.

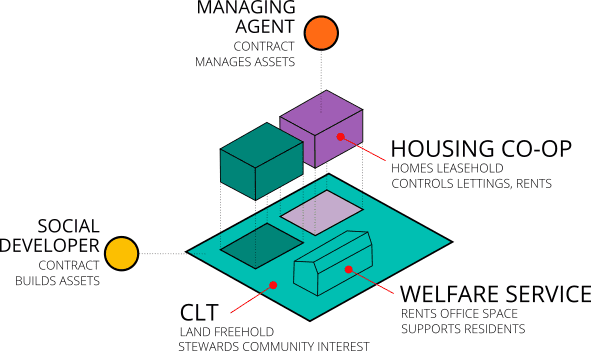

For example, look at this scenario:

Here, the functions of a housing association are broken apart into five different organisations that then work together. The CLT’s role remains the landowner and steward, while the development, management and maintenance of the homes and the provision of wider welfare services are run by four other organisations.

It’s not a million miles from the way some CLTs are working today, both in the UK and internationally.

For example, Yorspace CLT is developing a number of housing co-operatives and cohousing communities across York; the CLT owns and stewards the land, and enables each development; the residents self-manage their homes and community life through their own co-operative, with a lease on the properties from a CLT. Hastings Commons has developed an ecosystem of work space, social space and affordable flats in the town centre, with a JV company that buys risky asset and transitions them into a CLT as the long-term owner and steward.

My favourite example of this is Dudley Street CLT in Boston, USA, which I got to visit in March. The CLT owns 30 acres of land which it leases to a variety of affordable housing co-operatives, urban farms and commercial properties. It also works with the city council to steward local public open space and take forward a joint vision for developing remaining vacant lots. The surplus it generates from this portfolio, along with fundraising, supports community organising and community development work, with a particular emphasis on building power and capability among marginalised young and ethnic minority residents. It’s a holistic vision and collaborative practice for ‘development without displacement’, underpinned by community ownership of the land.

These are all experiments with forms of partnership rooted in community ownership of the land.

Functional pros and cons for housing

I think there are three functional advantages to this ‘Unix approach’:

- Each organisation can focus on getting really good at its one task – building to a high standard, maintaining homes so they don’t suffer from damp or fire safety issues, and so on. In the case of the CLT this is about much more than housing – their task is to develop an inclusive and participatory practice of commoning and stewardship, ensuring the land is best used for the long-term social, economic and environmental wellbeing of the community.

- If one function isn’t working well you can fix it in isolation, or swap it. For example, if the people managing their homes are no good then the co-op members can contract with a better managing agent. Private leaseholders can already do this with the Right to Manage, so why not all affordable housing tenants and residents?

- There can be a greater diversity of approaches to each function. For example, in a development of 500 new homes you can have an older person cohousing community, a student co-op and a private self-build group alongside standard affordable and open market homes. The self-build group might want to select a different developer to the rest, and each could find the right managing agent for them, or band together to form a common residential management company.

There may also be disadvantages to the Unix model of housing.

Currently larger housing associations use their ownership of their housing stock, plus their future rental income, to raise the finance to build new homes. Breaking the stock up into many smaller units might increase financing costs. Hundreds of small housing co-operatives developed in the 1970s and 80s collectively sit on assets worth an estimated £2.5bn, but they are each too small and financially conservative to do anything with them. (These problems could be solved with other ways of configuring the ownership and governance of the assets, and of aggregating finance.)

One of our members, WECH, started out with a partnership approach. The community took ownership of their land and homes from the council and partnered with a housing association to manage them. It later brought management in house to have more control, and led its own redevelopment and infill project. It became a more monolithic approach to the local commons.

I think we can do things better through these forms of partnership – we can achieve transformative things in partnership that we’re unable to do alone.

Aligning interests and control

Now the advantages I describe above are all functional – doing things better.

There’s another advantage which is about aligning ownership with interests.

One of the problems with the monolithic model is that all of these interests are squeezed into one governance structure.

Housing association boards are accountable to the regulator for good governance and financial management. In the wake of recent scandals the Government has (re)introduced requirements to report on the quality of the homes or the tenant service and to give tenants new means of redress if they’re unhappy. They’re accountable, in another sense, to the financial markets and the credit rating agencies that enable them to borrow to build. But there is no duty to consider the impact of their decisions on the communities local to their homes, or to consider how the land might be used to best serve the wider social, economic and environmental interests of that neighbourhood or parish.

Boards have a limited bandwidth, and many think that in recent years they have become too focused on major developments and credit ratings to the detriment of the day to day business of maintenance, or areas like community development.

In the Unix scenario, each functional unit is owned, controlled by and accountable to the people whose interests are most important: the land matters to the community around it; the homes to the people who live in them; and so on.

CLTs use their ownership and control to put the land into the commons, stewarding it for the common good of their local community.

This isn’t the commons as a free-for-all, descending into tragedy. It’s the commons with clearly defined boundaries – who the land should benefit, how people get access to homes, workspace, farmland, etc – and these are monitored and policed by the CLT. It’s a commons with participatory democracy at the heart – the local community organises themselves, writes their own rules and ensures the use of the land fits local circumstances. And it’s a local commons nested within a larger network of CLTs in their region and nationally.

This form of commons is appropriate for ownership and control of the land. The land should always be used for the benefit of the local community – for its social, environmental and economic sustainability.

In our current system we rely on the planning system to protect the interests of the local community. Or to reconcile those interests with the objectives of the housing association. But the planning system only bites when there is a major change – homes are demolished, built or substantially redeveloped. It doesn’t have any purchase on the ongoing use of assets. It relies on the application of complex policies that are rarely co-created by local communities in any meaningful sense – fewer than 1 percent of citizens engage in the Local Plan process, and around 3 percent engage in development consultations ahead of planning application submissions local to them. Most people who do engage are aged over 55 and are homeowners. The rest of the time the planning system has no purchase. There is little accountability to the local community.

Community ownership partly fixes this.

Community ownership of the land makes tenants and residents ‘co-developers’ rather than ‘users’ (to borrow the digital language). This applies not just to the construction of a new workspace or block of flats, but also the ongoing maintenance. Done well, given all the eyes involved all problems become shallow – spotting and addressing defects and identifying areas for improvement.

There have been lots of experiments with devolving or sharing power in the social housing sector – tenant management organisations, community gateways, tenant voice boards, and more recently CLTs. But they remain fairly marginal. The default and dominant model is monolithic and unaccountable.

The same is true of commercial, industrial, agricultural and recreational uses of land. Collaborative commoning is very rare.

Beyond the red line

Returning to my favourite example of Dudley Street, the other striking feature is that the CLT’s role is not limited to one particular housing development, one particular council asset transfer, one area of rewilded landscape. It holds land across the whole neighbourhood or parish or landscape, and is working towards that land best serving the neighbourhood’s whole needs – social, economic, environmental.

Kennett CLT isn’t just focused on the traditional ‘red line’ of the 500-home Garden Village development it’s currently involved with. Its area of interest, its area of membership, is the whole parish. It can integrate the new development into the existing, and go on to undertake other projects in the local area.

Very often CLTs develop multiple assets with varied partnerships. For example, Calder Valley CLT has built new homes with an almshouse charity; is renovating empty homes itself; owns a a Grade 2 listed community hall used by a separate community association; is working with Network Rail and the local station ‘friends’ group to restore a historic signal box; and is developing a new enterprise centre with the council.

I described the partnership between a CLT and a housing association above in terms of functions and interests. But there is also the spatial dimension. The housing association is principally interested in the dozen or so homes in the village, and in its wider portfolio which might spread across half a nation. The community hall operator is interested in just the one building. The CLT is interested in the whole community – in the different homes, community hall, signal box, enterprise centre, and looking to the future perhaps another brownfield site, an at-risk pub, some land that could be rewilded to reduce flood risk, and so on. Over time many CLTs expand their portfolio, as in Calder Valley, to continually develop towards a more thriving community – equitable, inclusive, biodiverse, etc.

In the UK we tend to support the creation of many small, monolithic social enterprises. When I lived in Crystal Palace there were separate community trusts for the library, park, community centre and housing, each trying to do a good job of asset management and service provision. I sometimes wondered – what if you pooled the assets into one trust – a CLT – which then leased them or had management agreements with groups who could then focus on the service? I also wonder at the wisdom of different trusts with narrow objectives – what if those trusts’ objects don’t enable them to address emerging needs?

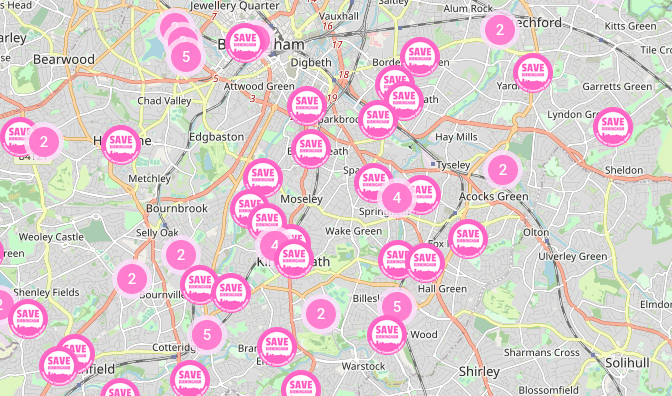

I thought of this, and CLTs like Calder Valley and Dudley Street, when looking at the excellent Save Birmingham campaign’s map of community places:

Many of these might naturally be of interest to existing local community organisations. Some might work well as standalone new projects.

But what if you took natural neighbourhoods across Birmingham and established half a dozen new CLTs, modelled on Dudley Street, with objects framed broadly around community development? They would take ownership of assets and work with different partnerships to achieve the best use. Those uses may change over time. The CLTs would also look to buy more land and assets in the area – perhaps there is a major regeneration project they could take a stake in, or some small sites they could develop with an SME builder.

Over time they would build, and adapt, a portfolio to best serve the community’s needs, directed and controlled by those communities.

Relational land governance

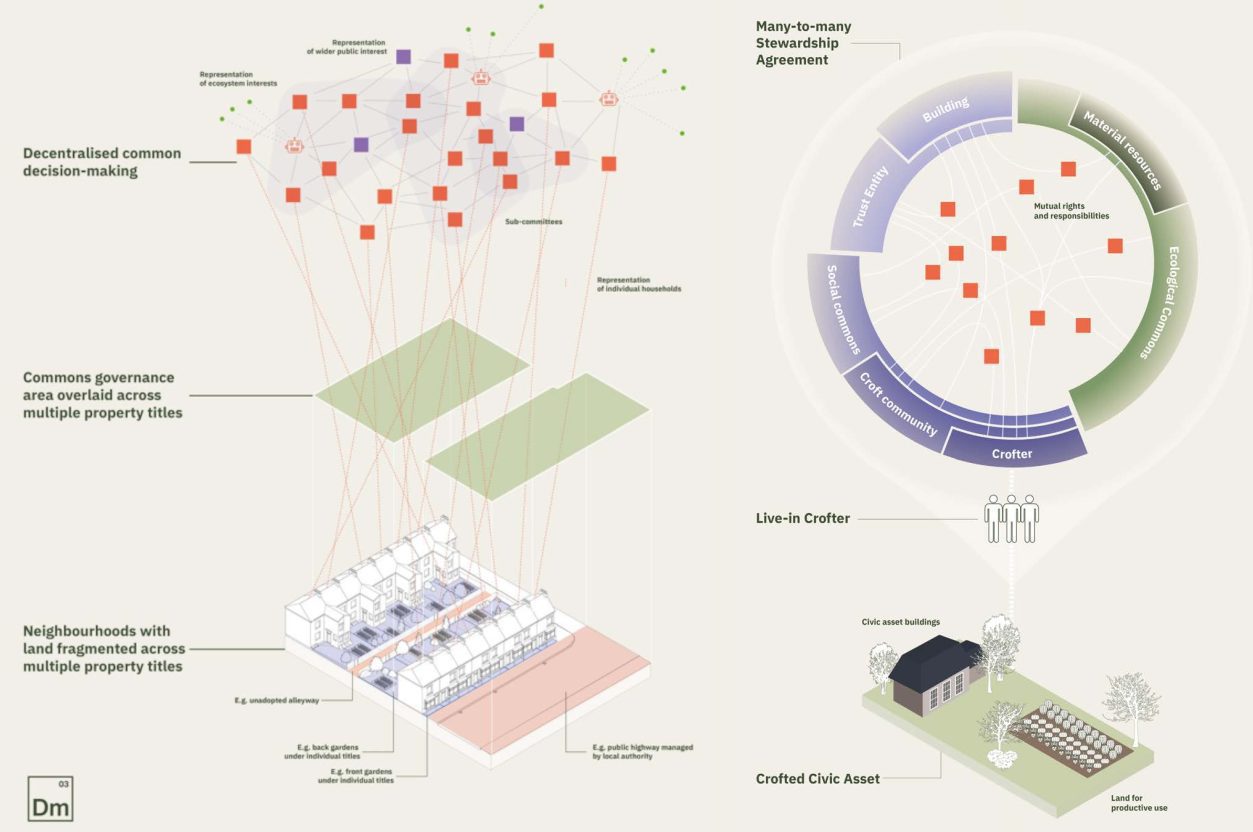

The Scottish Land Commission and Dark Matter Labs recently published a fascinating paper on land governance futures that takes us into the ethereal, and offers exciting ways to think even more broadly about breaking down monolithic models.

Taking different cultural and legal traditions from Scotland and elsewhere, they recast the concept of land governance entirely. Instead of thinking of a landowner as the primary agent, they consider the network of relationships that exist around and within land – the people and ecosystems the land affects. They then put forward some provocations of how we might rethink the governance of land to make those relationships reciprocal and generative. To give all those affected some appropriate agency, to connect them together, to direct their shared governance towards mutually positive outcomes, and to consider the emergent value that may be created through this approach.

You have to read the paper to grasp these ideas. I can’t do them justice in a summary. But their diagrams give a sense of the complexity and richness of the ways they are thinking about land.

Imagine, then, that you establish this network of CLTs in Birmingham to take ownership of the land and assets. They are charged with developing a democratic, inclusive and participatory practice of commoning around those assets.

You map the human and non-human relationships that intersect with that land and consider how the CLT’s own governance model, its arrangement of leases and management agreements, its partnerships, can best achieve ‘commons stewardship’.

You partner with community centre operators, friends of parks groups, makerspaces, housing associations, private developers, schools, the council to operate and further develop assets in your portfolio.

You invest in community organising as much as community assets – building a diverse and inclusive participation to enrich the stewardship of assets. You build power and capability across the community.

And under it all sits your land. Owned by the community, through a CLT. Held in trust for the long-term social, economic and environmental wellbeing of the community.

Are you on board?